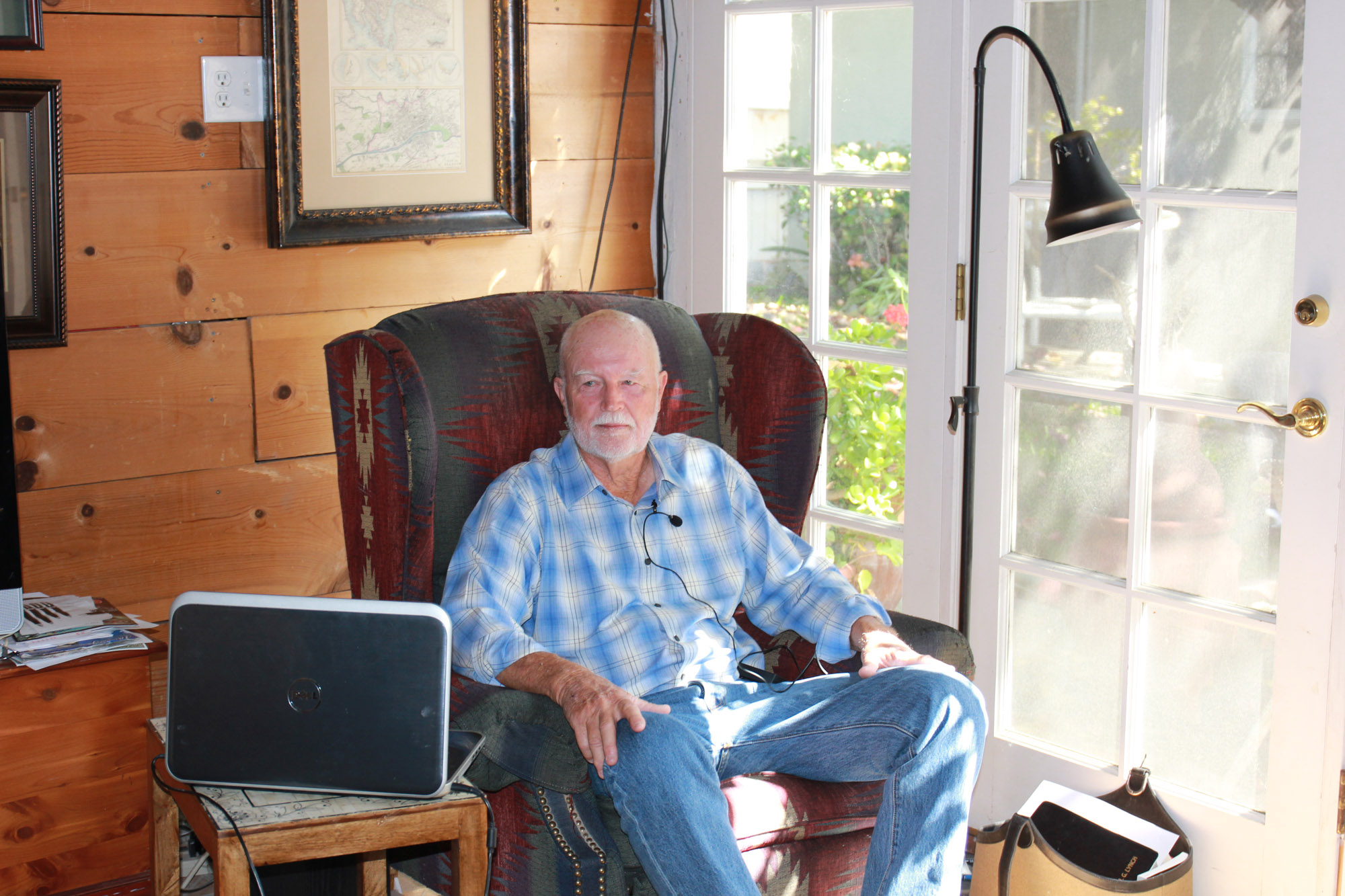

James McMichael Go to Transcript

Location: Long Beach, CA | Date: March 17, 2014

James McMichael was born in Pasadena, California and received his Ph.D. at Stanford University. He... Full Bio and Bibliography

"My files are up here to the right. They're artist sketchbook, so they're unlined. And I take notes from the reading I do in those, and I also include (in green ink) my own responses to the things I'm reading, or things that occurred to me that might turn out to be germs for lines."

From interview

section 1, "Devices and Digital Practice"

0:00:00

"He's a genius. He's an expensive genius. His name is Steve Marinoff. We're entirely dependent on him—Susan and I for having these machines continue to work—and he's never failed us."

From interview

section 2, "8 Year relationship with hired 'Tech'/personal IT professional"

0:05:12

"but after about 2 years in the job, I started writing quite bad poems—and they continued to be bad poems until I'd completed a book of them. I submitted it for publication. It was accepted. It turned up in the mail. I sat down and read it, and it confirmed what I knew about it which was that it was a really bad book of poems."

From interview

section 3, "Beginning of Career to First 'Bad' Book"

0:06:54

"I needed to teach myself how to write a paragraph. I didn't know how to write a paragraph. I knew how to write a paragraph in graduate school prose, but not a paragraph. Those are different things, so that took quite a while."

From interview

section 4, "Publication history of poetry collections and critical work on Ulysses"

0:10:16

"for me, since I tend to work in an extended (what can seem like) book length forms almost all the time, then any individual poem I'm working on has a necessary relationship to everything else I'm imagining."

From interview

section 5, "Relationship of organizational/archival activities to writing process"

0:12:50

"[T]here wasn't anything I could alter until I asked myself if there was something I needed to write about rather than just my own insecurities as someone who didn't know how to write a poem."

From interview

section 6, "Early career writing practices and difficulties"

0:15:10

"After I wrote the Vegetables, I had a standard that I had to apply all the time. And once it was in place, then I had something to work with besides form."

From interview

section 7, "'The Vegetables' as guiding model and Generating in Book-Length Terms"

0:18:46

"I can't imagine how it was possible to write a book of prose (to write the Ulysses book) long-hand with a typewriter."

From interview

section 8, "Early career longhand and typewriter writing practices"

0:23:15

"And then, it would have to be revised. Pretty soon, it would be better enough maybe to stay, and then when I'd get (I don't know what) 8 or 9 lines more, then I'd go to the typed copy of what I'd transcribed from long-hand on to typed copy and add what was new, make what changes I'd made in long-hand, and then just bring all of that along with me."

From interview

section 9, "Step by Step Writing Process from longhand to typewritten"

0:24:45

"I work on them almost only cumulatively so that I take them along line by line. I don't...I'm not able to write a draft of something."

From interview

section 10, "Simultaneous Revision and Composition Process"

0:30:50

"That was all I had. I didn't have a page a year, essentially.And for the life of me, I don't understand why I didn't just accept that I was thru writing."

From interview

section 11, "Beginning and Continued Composition of a Book"

0:34:22

"These are the notes that I would take for the book that I'm reading. The RED is the more important material. It's something that, if I'm going through it I can read and just pick out the highlighted parts, then GREEN are my own responses. So, I'm always working on the right hand page when I'm taking notes from books I'm reading, then when I'm going back over the material, I'll work on this [left-hand] page and there'll be other changes."

From interview

section 12, "Note-taking Practice in notebooks and on cards"

0:37:59

"And then that gives me a sense that there's less I've failed to address, and therefore maybe I've been brought to a position (with their help) of being able to find a phrase that lets me move from this point, in where I am with the poem I'm writing, further along."

From interview

section 13, "Suggestive Importance of Reading to Practice"

0:44:58

"But it seemed like it was very easy transition—I don't miss the typewriter, which I loved, you know? But I don't miss it—I think it's in my storage space about 2 miles away from here."

From interview

section 14, "Latest Book Being Composed on Computer rather than Longhand and Typewriter"

0:48:00

"But I love how non-invasive this [the computer] is as a medium—not so much in terms of my being protected against being invaded by somebody else, but being able to say something (send somebody something here [on the computer]) and understand that they can open it when they want, and that it's not an imposition on them."

From interview

section 15, "Transferring Processes to Computer for Poems and Letters"

0:50:13

"You know, it has to be—it just has to be. What can your ear bear here? And if it can bear it, is it saying what it has to be saying?"

From interview

section 16, "Revision by Ear and via Correspondence"

0:52:45

"I've really liked the way the computer makes it possible to re-lineate poems that I've gotten from students—just to give them a sense of how I hear what they're doing with the lines."

From interview

section 17, "Critiquing Work from Others on the Computer"

0:55:00

"What do you consider the product? The poem that I can't make any better."

From interview

section 18, "Primacy of the Poem as Product in Book Composition"

0:56:19

"And I would want form, which in my case is the line and the stanza, to instruct a reader of that book on how I hear the phrases and the sentences."

From interview

section 19, "What is the Product and Where Does it Exist"

0:57:25

"Yes, I feel naturally, inherently bad at it."

From interview

section 20, "Internet's (lack of) Impact on Writing Practices"

1:00:22

"Then Hendrix was dead and The Stones weren't what they had been. At that point, I had a need for music that got to me, and there wasn't any more of it coming from jazz or rock, so then I started learning classical, learning the literature of classical music, and it's had hold of me since November of 1973. You know, I feel that it's trained my ear to be what it is. I don't know how it's done that but it's been elemental to me."

From interview

section 21, "Development of Aural Acumen by Listening to Music"

1:01:51

"So, variety is one of the models but that was the form."

From interview

section 22, "Schoenberg's 12 Tone System as Formal Model"

1:06:10

"I think there's a non-accidental relationship between the forms I was working with having been as short as a 3-minute take and a sonata form, or a scherzo trio form, or an adagio, or something like that that the lengths of it (the units I was working on ) got larger when I was listening to pieces of music that were 8-9 minutes to �_ an hour long."

From interview

section 23, "More on Classical Music's Positive Effect on Writing"

1:08:35

"And I like the fact that it's this keyboard that connects me with them, and this keyboard that connects me with strangers who might read my poems. I like that about this—a lot. I like it a lot."

From interview

section 24, "Thoughts on Computer's Impact on Teaching and Social Relationships"

1:10:32

Interview Materials

Writing Process Visualization (View All)

Process Narrative Excerpt:

"James McMichael works, almost primarily, in extended, book-length form. As he says, "any individual poem I'm working on has a necessary relationship to everything else I'm imagining." He brings his poems along line by line and his books along poem by poem, writing "chronologically" until..."